A strong and principled family caught up in the febrile atmosphere of the First World War

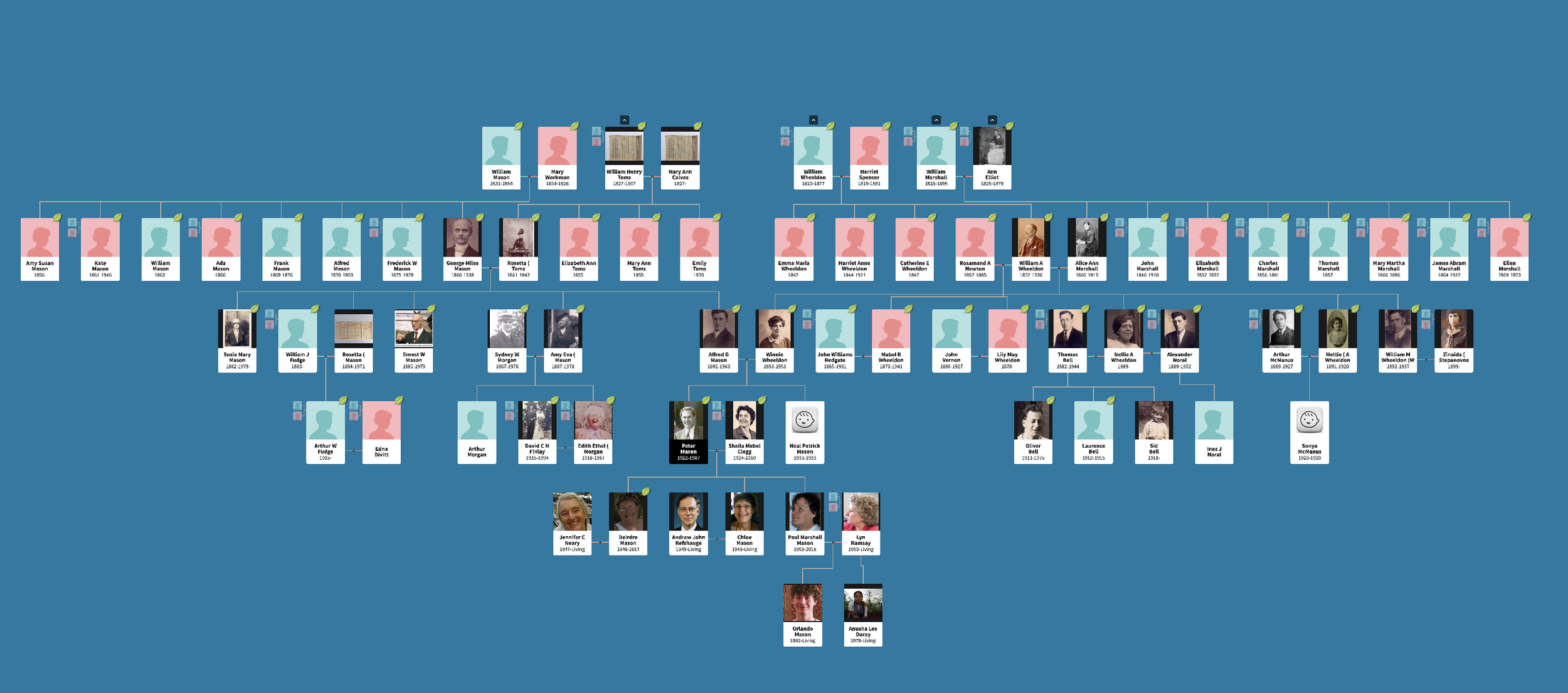

Alice Ann Wheeldon, principal defendant: charged and convicted

Winnie Mason, Alice’s youngest daughter: charged and convicted

Alf Mason, Winnie’s husband: charged and convicted

Hettie Wheeldon, Alice’s second daughter: charged but acquitted

Nellie Wheeldon: Alice’s eldest daughter

Will Wheeldon: Alice’s son

Alice Ann Wheeldon (née Marshall) (1866–1919)

Alice Marshall was born in Derby in 1866. In 1886, she married William Augustus Wheeldon, and the couple moved to Bootle, near Liverpool. Over the next few years Alice Wheeldon gave birth to Nellie (1889), Hettie (1891), William (1892) and Winnie (1893).

The family moved back to Derby in 1894, and in 1901, with the inheritance from her father, William Marshall, Alice took over an established business as a ‘wardrobe dealer’ at 12 Pear Tree Road.

As the main income earner for her family, she supported the household through buying and selling high-quality second-hand clothes, and she rented the small semi-detached house where they lived. Family letters relate the daily work of mending clothes and putting food on the table, as well as the news from the neighbourhood where Alice was a “well-known sympathiser with the suffragists”.

Leaving school herself at the age of 12, “Mrs Wheeldon was always determined to give her children the best education she could”. The many family records (books, letters, paintings, newspaper articles, archives) show that her children worked, participated in public speaking, engaged in word games and jokes, enjoyed rambling in the Derby Dales, learning and cats, rode bicycles and retained a commitment to justice. Alice and all four children were awarded (and kept) medals for first aid and life-saving. This close-knit family were honest and humorous rapporteurs of their world.

Nellie, Alice’s eldest daughter, worked in a co-operative health food shop and was active in the co-operative movement. William (‘Will’), Alice’s son, attended Nottingham University and became a schoolteacher. Daughters Hettie and Winnie trained as school teachers in London, and taught in Derbyshire. After her marriage to Alf Mason, Winnie taught in Southampton, where Alf was a lecturer in chemistry.

Alice and her children were socialists, pacifists and anti-war campaigners, vocal in their opposition to the continuing and pointless carnage of the First World War.

She was extremely anxious about the safety of her son Will, a conscientious objector, and the uncertain outcome of his court martial, which was decided while she was in custody, on 26 February 1917.

By December 1917, Alice Wheeldon, convicted and imprisoned, was angry and “inveighing against her 10 years sentence” by ‘self-starvation’. Dr Paton, the examining prison medical officer, reported:

“She says she has a clear conscience and that her trial was atrocious faked evidence. She says she is determined to get out of prison ‘in a box or otherwise’. She swears she will never again put on prison clothes, ‘By God! I won’t’.”

In failing health, she was released from prison on licence in December 1917, and died in 1919.

Winnie Mason (née Wheeldon) (1893–1953), teacher

Winnie, Alice’s youngest daughter, was born in Blackburn in 1893. Like other members of her family, she was a pacifist opposed to the First World War.

Winnie married Alfred Mason in 1915 and moved to Southampton, where she worked as an elementary school teacher, at Foundry Lane Boys’ School. She had matriculated with a certificate in chemistry and at the time of arrest was enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) at London University. Like her elder sister, Hettie, Winnie had trained as a teacher at the British and Foreign School Society’s Training College for Mistresses, in Stockwell, London.

Winnie was arrested in front of her class. Her reaction was of surprise: “What is it all about? I don’t understand it.” Responding to the Clerk’s query at being held on remand, she said: “I think it is an infamous concoction against my family and my husband.”

On the eve of the Old Bailey trial, according to her close friend and undergraduate classmate, she appeared stoical, placing her faith in justice.

In custody and after conviction, Winnie felt powerless and was pained by her inability to intercede for her ill mother.

Winnie’s health continued to deteriorate in HM Prison Liverpool and she spent 12 weeks in the prison hospital. Friends provided support with one friend writing to say she had collected 150 signatures petitioning for Winnie and Alf Mason’s release.

At the end of war in 1919, Winnie and her husband were released from prison. They joined sister Nellie and friends in Croydon, London, where they worked for a short period in the family dairy business.

Eventually the family moved back to Hampshire, to Bournemouth, where their son, Peter, was born, and where Winnie was noted for raising awareness of the rise of fascism. Throughout her life, she continued to be active in left-wing movements.

In 1949, she took up residence in Welwyn Garden City where Alf had built a modern house in the new town. She was diagnosed with lung cancer and died there on 13 May 1953.

Letters from Winnie Mason indicate that she was searching for Nellie Wheeldon in the USA and for Will Wheeldon in Moscow until her death.

Alfred George ('Alf') Mason (1892-1963), pharmacist

Alf Mason, the son of Rosetta and George Miles Mason, was born in Southampton in 1892. His father was an astronomer and an optician who also made lantern slides. In 1908 he was apprenticed to a chemist in Southampton and at the age of 20, began work at the Analytical Department of Guy's Hospital in London.

He married Winnie Wheeldon in 1915, and the couple settled in Southampton, where he worked as a chemist. He was also employed as a lecturer in pharmacology at Hartley College, Southampton.

Alf was a conscientious objector to the First World War and feared that he would be conscripted. Along with Winnie and the rest of her family, he was a member of the No-Conscription Fellowship (N-CF) supporting conscientious objectors.

Alf was arrested in Derby with his mother-in-law, Alice Wheeldon, on 31 January 1917, charged with conspiracy to murder.

While awaiting trial in Brixton Prison, he was separated from his wife, and isolated from his sister-in-law Hettie, who was organising the defence, as well as from Alice. Alf demonstrated a strong sense of responsibility for his wife’s family, doing his best to obtain funds from his own (wealthier) family and find friends who would come to the trial as defence witnesses.

He was convicted and sentenced to seven years, but released in 1919 along with his wife and imprisoned conscientious objectors, including Will Wheeldon, after an active campaign to free them, led by Hettie.

Alf had become ill while in custody and took a long time to recover physically after his release. Although he resumed his profession as a chemist, he led an unsettled, rootless life on release, with long periods away from his wife and child.

His granddaughters, Chloë and Deirdre Mason, recall visiting the pharmacy in Holborn where he was working, and his sudden visits to the Mason home where Winnie was living. They knew that Winnie, their grandmother, had been in prison, but presumed this was as a suffragette. They were not told of Alf’s equivalent prison experience until 1986.

When Winnie died in 1953 Alf moved back to Southampton and lived with his brother in the family home. He and his brother Ern built a huge telescope in their backyard which was gifted to the Follands Astronomical Society.

Alf died of cardiac failure in London 1963, aged 70.

Harriett Ann (‘Hettie’) Wheeldon (1891–1920), teacher

Born in Bootle in 1891, Hettie Wheeldon was Alice’s second daughter. She was an elementary school teacher in Ilkeston, Derbyshire at Bennerley Avenue Boys’ School, and engaged to a Derby toolmaker, Walter Goodman, who held occupational exemption from conscription.

During the early years of the war, Hettie was secretary of the Derby Clarion Club and, for a short period, secretary of the Derby branch of the No-Conscription Fellowship (N-CF). Highly principled, she was appalled by the absurdity of the charge she faced – conspiracy to murder. While in custody, she wrote to the mother of a CO in Wakefield Prison:

“For myself I do not mind this persecution. I must say I expected it and have expected being arrested for months now with regard to aiding and abetting COs, but the monstrousness of this charge is its own failure. No one who knows us, believes it...”

She was also hurt and humiliated when a Derby newspaper reported in detail a church sermon in which she and Winnie, two school teachers, were condemned as ‘subtle tempters’ leading children astray. She wrote to the minister at the church requesting a retraction, and appealed to the DPP to take action.

At trial, she testified that she had been contemptuous of ‘Gordon’’s suggestion to her to assassinate political leaders. She took notes and later produced a critical analysis of the trial in a 60-page report that constituted a passionate, reasoned and comprehensive (at that time) condemnation of the trial. She argued, for example, that ‘it is highly unjust not to call an important witness’. In her report, she quoted material from the Parliamentary Papers and debates about case law in an intellectual weekly magazine, New Witness.

On acquittal, Hettie sought care for her ill mother in prison throughout 1917 until Alice was released on licence at the end of December. With her sister Nellie and a local friend, Hettie then accompanied Alice back to Derby.

She created a pamphlet, ‘Victims of Alex Gordon’, for the campaign to gain release of both Winnie and Alf Mason, with support of the Derby MP J.H. Thomas. The War Office instructed the leaflet was not to be sent beyond the UK.

In June 1918, concerned by the fact that Winnie was ill and in the prison hospital, Hettie organised a prison visitor for her. This was arranged through the Bermondsey (London) Board of Guardians, even though Winnie had been transferred to HM Prison Liverpool. Hettie also petitioned the Prison Governor for her release.

Although acquitted, she was barred from teaching after the trial.

She married Arthur McManus in 1920, and they had a stillborn child. She died from peritonitis following on from appendicitis the same year, at the age of 29.

William Marshall (‘Will’) Wheeldon (1892–1937), teacher

William Marshall Wheeldon, the son of Alice Wheeldon, was born in Bootle in 1892. Trained as a school teacher at Nottingham University, he taught at Traffic Street Council School, Derby. He was a water polo player and competitive swimmer. He and Hettie both supported the campaign for ‘mixed bathing’. He joined the No-Conscription Fellowship in 1914 and became a conscientious objector in 1916.

By December 1916, when ‘Gordon’ approached the Wheeldon household, Will had already spent three months in prison and was in hiding, working on a smallholding near his sister Winnie Mason in Southampton. As a CO, he was court-martialled just before the Wheeldon trial and sentenced to 18 months hard labour.

He encouraged his mother to seek outside support, to see the prison doctor about her pre-existing heart condition, and to request visits by the Quaker chaplain, Herbert Corder.

On his release from Durham Prison in 1919, he was excluded from teaching in England, and joined a Quaker famine relief mission, the Friends Emergency War Victims Relief to Buzuluk, Russia. He stayed on, marrying a young Russian woman and becoming a citizen of the Soviet Union in 1926, teaching and working as a translator for the Comintern.

Stalin had him arrested on 5 October 1937 as a strong supporter of Trotsky, and the Military Board of the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death. He was executed by firing squad in Lubyanka Prison Moscow on 25 December 1937.

News of Will Wheeldon’s execution in 1937 in Moscow was only released by the Russian security ministry in 1992, as part of Perestroika. Michael Durham describes the discovery in The Independent, ‘Death of an English Socialist: Moscow helped solve the mystery of William Wheeldon, who fled to the Soviet Union in 1921 to escape persecution’, 12 September 1992.

Nellie Wheeldon (1889- ?)

Nellie Wheeldon was born in Bootle, Derbyshire, in 1889. She was Alice Wheeldon’s first child.

In Derby, Nellie first worked in a health food shop owned by her friend Dorothy Robinson (nee Groves); the Robinson family were friends of the Wheeldons and in late 1916 had also been visited by the same undercover agents.

At some stage, Nellie worked in the fruit department of the Derby Co-operative Society shop East Street.

In 1914, just before the war, Nellie participated in a national co-operative summer school, held in the Lake District, having won a scholarship from an essay-writing competition. The Co-operative Record published her short article commending the co-operative movement and workers education and indicating her involvement in ‘platform oratory and newspaper work’.

Little is known of Nell’s early life but we know that she was active politically with the rest of the family in the suffrage and socialist movements of the time.

With the arrests of her family at the end of January 1917 and intense, hostile publicity, Nellie moved out of the family house to the safety of a neighbouring aunt.

After the death of her mother she joined the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain in Derby in 1921. Later she moved to London and in 1925 was living with Tom Bell in a group household in Kensington with other members of her family, who had been released in 1919, and worked in Alf Mason’s pharmacy.

Some time after the 1926 General Strike, and Tom Bell’s release from prison, she travelled to the Soviet Union and worked as a corrector in the English Section of the Comintern.

After returning to England, she left for the USA in 1931. She lived in San Francisco where she joined the Workers Alliance of America and became an organiser for a women’s trade union of laundresses. No trace has been found of her since 1938.